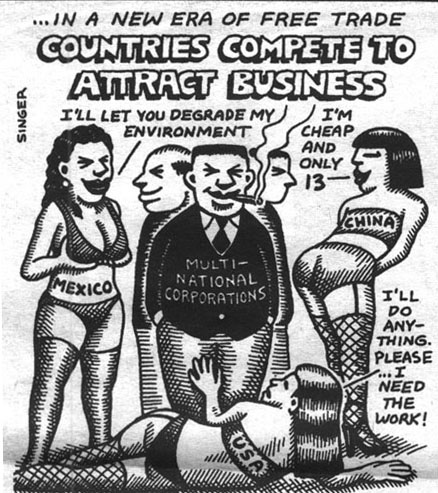

And When You Get Your Factory Built, Would You Like to Rape My Sister?

By Hardly Waite, Gazette Senior Editor

Not long ago, our fair city, as Click and Clack would say, was embroiled in a big controversy about a zoning permit granted by the city fathers to a wealthy Mexican company with more than a few shady deals in its past. The corporation, which planned to build a copper smelter (although they never, ever called it that), had wined and dined the city council who, save for a single councilman who was able to keep his wits about him, were so in love they were ready to skip all the usual formalities and get right on with the wedding.. Never mind that the proposed plant was to be a lead-belching smelter and its smokestacks had a straight and close downwind shot at a large elementary school.

By the time a citizens group formed to oppose the plant, stopping the project seemed hopeless. The deed had already been done behind closed doors. The Texas environmental regulatory agency, made up mainly of chemical company executives appointed by still Governor W. hisself, had already rubber stamped the permit request, and the “light industry” zoning, absurd as it was, had been granted by the city council. It looked as if “Free Trade” had triumphed over the ignorance of small-town Luddites who would have held back progress over such a trifle as the selfish desire to breathe reasonably clean air.

But as if to show that, in spite of appearances, the world is not always unjust and illogical, things didn’t turn out too badly. By persistence and some costly litigation, the citizens group, though unable to stop the smelter’s construction, was able to severely inhibit its freedom to smelt. And, Fate be praised, the copper market went so sour that once in production the company had trouble selling the reduced amount of copper it was able to produce. The Mexican owners even fired the pushy CEO who had rammed the project down our throats because he wasn’t making a profit. Now the plant is there but it doesn’t belch much smoke.

Although because of a lot of hard work and sacrifice by “environmental whackos” the outcome wasn’t so bad, the whole episode reinforced my long-held belief that by promoting our cities to woo industrial development we are usually being our own worst enemies.

Here are some cuts from an article by Ted Rall that will illustrate. It’s about his experience in the late 1980s when he worked as a U. S. representative for a Japanese bank that was looking for places to put up factories for its customers in the United States. Here’s how he went about it:

First, I’d run a comparison of employment statistics of towns in areas that were convenient for the company, taking into consideration criteria like being near a highway or one of their suppliers. Target communities would have high unemployment, low wages, no unions, and lax environmental enforcement. It is amazing to see how states compete against one another with brochures like Tennessee: A Right-to-Work State with Minimal Union Activity! These officials, whose salaries come from taxpaying workers, have no interest in seeing their citizens earn a living wage. All they want is more jobs, regardless of the cost or the quality of the jobs.

Then I’d practice my best local twang, the intensity of which was directly proportional to how far south I was calling. I’d call the three top candidates for a plant and let them fight like weasels over a few low-wage jobs. Once, when a chemical company needed a fairly educated workforce, I called the Economic Development Office of Moraine, Ohio, a stone’s throw from where I grew up:

Me: Hi! My name is Ted Rall and I’m a loan officer at the Industrial Bank of Japan in New York. [I’d say Nyew Yerk.] I have a client that wants to build a twenty-million-dollar plant in Moraine. They’ll be hiring fifty people. [Untrue—it was probably more like 20, but by the time the plant was finished, it would be too late to complain.] Can you waive your property taxes?

Moraine: Sure, we can do that, no problem. We normally waive property taxes and utilities for ten years. [There goes a few million for the local schools.]

Me: What about roads? My client’s plant needs an access road and its own entrance to Interstate 75.

Moraine: we can build a ramp for your client. [For about $5 million. Oh well, the rest of the city will have a few more potholes.

Me: There’s a sewage problem—there are no lines on the property. We’ll need you to pay for them.

Moraine: Okay. [If a private citizen built a house there, he’d have to pay for the hookup himself.]

Me: Also, many of their employees are Japanese. Can you establish a Japanese-language school for their kids? [I’m going for the gusto—this one is not that important.]

Moraine: we don’t have that.

Me: Tennessee will do that. [True.]

Moraine: I’ll look into it. [My client, which enjoys annual profits of more than $150 million, has just saved about $8 million. Should they choose to locate there, maybe they’ll buy some lame painting with the extra money.]

Although the company in this particular deal eventually built their plant in another city, this routine goes on every day in every community in the United States. (In my experience the only state that won’t sell its citizens’ wage and taxes down the river to whore for some business is Massachusetts. It’s not that interested in “economic development.”) There are no genuine net benefits to granting concessions to a company to build in your community. You don’t collect any taxes, you pay millions to bring roads and sewers to their door, and chances are that they’ll leave in less than ten years anyway. On the other hand the toxins they leave behind will be around a very long time.

Denton City Manager

“When you guys finish your copper smelter, would you like to rape my sister?”