Research: Fight against bacteria is harming environment and humans

By Judy Benson

Unregulated, potent, germ-killing chemical triclosan, commonly found in cleaning products and cosmetics, breezes through sewage treatment plants to enter waterways, including Thames River

Editor’s Note: The article we’re reprinting here from The Day focuses on the essentially useless and potentially very dangerous “antimicrobial” chemical called triclosan, but the overall issue involves the many unregulated chemicals commonly found in cleaning products, antibacterial soaps and additives, cosmetics, articles of clothing, and regular household items that are collectively referred to as “emgerging contaminants.” The problem is that the “emerging contaminants” are being introduced into the environment much faster than regulating agencies can evaluate their safety. This poses a weighty problem for wastewater treatment facilities. – Hardly Waite.

Every time you brush your teeth with Colgate Total, coat your underarms with Arm & Hammer Essentials deodorant, or wash your hands with Dial Complete liquid soap or your dishes with Dawn Ultra, you may be polluting the Thames River.

These and dozens of other cleaners and cosmetics, along with toothbrushes, socks, underwear, yoga mats, hockey helmets, cutting boards and other items carrying labels like “Biofresh,” “Microban,” and “antimicrobial,” contain triclosan. This powerful chemical kills bacteria but also is the target of growing concern about its harmful effects on human health and the environment.

This summer, The Day worked with University of Connecticut environmental engineering professor Allison MacKay to collect and test samples from the river and from the effluent that’s discharged into the river by the region’s largest sewage treatment plants. For the past year and a half, MacKay has been researching the presence of 11 chemicals from medications and cleaning products, including triclosan, in two other rivers in the state. In the Thames River tests, triclosan showed up in three of the four wastewater samples.

University scientists take samples from Connecticut’s Thames River

“This is a stupid use of a toxic chemical,” said Mae Wu, attorney for health programs at the Natural Resources Defense Council, a nonprofit group with a pending lawsuit to force the Food & Drug Administration to regulate and curtail use of triclosan and its close cousin, triclocarban.

First introduced into products in the 1970s, triclosan became a common ingredient in the 1990s when antibacterial hand soaps became popular, but the FDA, which declined to comment on this story, has left it unregulated.

As the use of triclosan has increased, mounting evidence has shown that the chemical may interfere with important hormonal processes in wildlife and humans, and it may spur the growth of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, Wu said.

“The government needs to say it’s safe or get it off the shelf,” she said. “Why are they making guinea pigs out of all of us?”

The problem with triclosan – and with other chemicals in pharmaceutical, health and cleaning products used every day – is that sending it down the drain means tiny amounts enter the environment. Traces of antidepressants, birth control pills, pain killers and other medicines have been found in treated wastewater – samples that appear crystal clear and meet all state and federal quality regulations – as well as in the waterways that receive the discharges. These are the leftovers of drugs that people take every day, but that don’t get fully metabolized. Instead, they pass through with urine, get flushed into sewage treatment systems and emerge in minute quantities at the end of the process.

Collectively known as “emerging contaminants” or “contaminants of emerging concern,” these byproducts of human consumption are getting a lot of attention from researchers worldwide who are trying to understand what their presence means for wildlife and people.

“People are often surprised to find out that when you take drugs, your body doesn’t use all of it,” said MacKay, who has been focusing her examination of wastewater and river samples from Vernon and Southbury on how emerging contaminants break down in sunlight. “There’s no question that many of these pharmaceuticals have some very important public health benefits. But wastewater treatment plants were not designed to remove these compounds.”

‘Committed to the environment’

In August, MacKay and The Day collected samples from the Thames and from four of the five sewage plants that empty treated wastewater into the river. Officials at the Montville plant refused to provide a sample of treated effluent for the project, citing concerns that the results would lead to orders for new and costly upgrades.

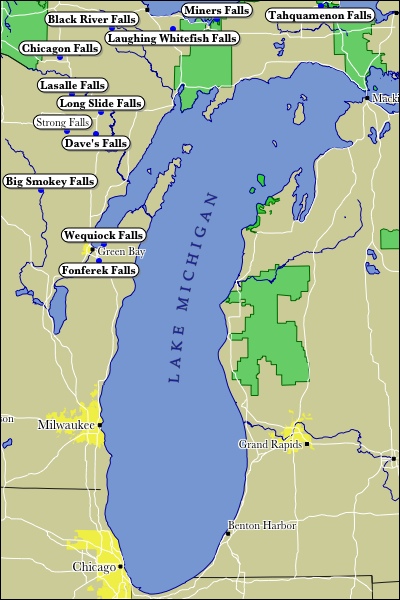

The Thames, a large tidal estuary that flows from Norwich to New London and empties into Long Island Sound, is much larger and more complicated than the other rivers MacKay has tested. At the outset, she acknowledged that because of this, the chances of finding traces of any of the 11 compounds – including antibiotics, over-the-counter pain medications and triclosan – were slim. Indeed, the river water tests, collected at three depths near the Norwich and New London wastewater outfall pipes on a bright, late summer day, revealed no detectable quantities.

“It’s a little bit like finding the needle in the haystack,” she said after a morning boat trip on the river to collect the samples.

Just because the needle doesn’t turn up after a single search of the haystack doesn’t mean the needle’s not there. A week after the river samples were collected, The Day visited the Norwich, Groton Town, Groton City and New London wastewater plants, al of which agreed to provide samples of treated effluent just before it entered the river. The samples had been through the multi-stage settling, biological and chlorination processes at the plants that remove all the obvious contaminants people send down their drains every day.

“We’re the first responders to human health,” said Kevin Cini, chief plant operator of the Groton City plant, which discharges 2 million gallons of treated wastewater daily into the Thames. “I tell young people who tour the plant all the time that (emerging contaminants) are probably the next thing we’re going to have to bes dealing with.”

At the New London plant, where 6 million gallons a day from the city, Waterford and East Lyme are treated and discharged into the river daily, Joseph Lanzafame, director of public utilities, said he and other plant operators are looking for direction from federal and state regulators as to what to do about emerging contaminants.

“If these things end up being regulated, we’ll upgrade,” he said. “We’re committed to the environment.”

Highest level in Groton City

After samples were collected from the four plants, they were stored on ice and taken that day to the Environmental Engineering Lab at UConn in Storrs. There, Laleen Bodhipaksha, who is pursing his doctorate in chemistry, began the tests.

Bodhipaksha has been working with MacKay, running dozens of the advanced, highly sensitive tests known as ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. As the name suggests, it is a multi-step, complicated process requiring expensive equipment and advanced analytical chemistry skills.

It is only over the last 15 years or so that the techniques and equipment needed to detect minute quantities of drugs and consumer chemicals have become available, MacKay said, so in many ways, the technology has driven the rising concern about emerging contaminants. They’ve been getting into waterways for years, but no one knew.

“It’s a new problem, but it’s not a new problem,” she said.

The tests detected triclosan in the samples from Norwich, Groton City and New London. The Groton City sample, which had the highest level, also contained small amounts of ibuprofen – the main ingredient in Advil and Motrin – and gemfibrozil, a blood pressure regulator. None of the 11 compounds showed up in the Groton Town sample, probably because of the four, that plant has had the most recent upgrade and is able to treat to a higher standard the 2.9 million gallons a day it takes in, John Carrington, Groton’s manager of water pollution control, said.

MacKay said the levels of triclosan, ibuprofen and gemfibrozil locally were in the same range she has seen in her other testing, and also were similar to national results. Since the triclosan is in the treated wastewater, it’s clearly getting into the Thames, which daily receives about 18 million gallons of effluent from the five plants. True, the tests found what amounts to a tiny speck of the stuff per bucketful – 493 nanograms per liter was the highest level found – but day after day, in a steady stream, those specks taken together may be significant.

“This is definitely a compound that’s high on our radar,” said Dana Kolpin, senior research hydrologist and team leader at the U.S. Geological Survey’s Contaminants of Emerging Concern Project. “It’s fairly common to find triclosan in effluent, but the big question is, in these concentrations, does it mean anything?”

Kolpin, who began researching emerging contaminants in 1998, is considered one of the nation’s experts on the issue. He noted research that shows triclosan can spur the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, as well as findings that it degrades in the environment into methyltriclosan, “a dioxin-like compound.” Dioxin exposure can cause cancer and immune and developmental disorders, among other effects.

“It’s not just the active ingredient,” Kolpin said. “It’s that it can degrade into something just as bad. It’s very tricky chemistry.”

Triclosan, he said, is an unnecessary product additive. It washes out of socks and underwear treated with it, and liquid soap with triclosan doesn’t work any better than hot water and soap at getting hands clean and bacteria-free, he said.

“We’ve gone crazy with these products,” he said. “We just don’t need them.”

Marc Zimmerman, hydrologist at the USGS’s Northborough, Mass., office, said one of the issues with persistent triclosan contamination is that the chemical is causing incremental changes in ecosystems. He studied the issue in Cape Cod’s waterways.

“It’s disturbing the bacterial ecology,” he said.

Company reactions

At the National Association of Clean Water Agencies, a professional organization of 300 municipal wastewater treatment plants, curtailing the use of triclosan is considered a “no-brainer,” Chris Hornback, the group’s senior director of regulatory affairs, said. Figuring out what to do about all the emerging contaminants may take more research and significant effort on the part of regulators, but enough about triclosan is already known, he said.

“It’s a good place to start,” Hornback said. “We need to do more to limit how much is getting into the systems in the first place.”

In May, his group sent a letter to an Environmental Protection Agency panel reviewing triclosan.

“NACWA members are concerned about the environmental impacts of triclosan in wastewater and the potential of triclosan to harm the beneficial micro-organisms that treat wastewater,” wrote Cynthia Finley, director of regulatory affairs for the group. In other words, the chemical may be killing off the good bacteria that are key to the treatment plant processes, potentially causing plants to fail water-quality tests, “resulting in substantial costs for utilities.”

Since treatment plants have no control over what comes in, Finley argued, EPA and FDA regulations limiting use “are the most practical means of controlling discharges of these chemicals into wastewater and preventing adverse impacts to (plants), human health or the environment.”

The nonprofit Environmental Working Group is a strong ally of NACWA’s position. Citing evidence from its own water tests in San Francisco and tests of blood samples from 20 teenage girls showing that triclosan and other emerging contaminants are getting into the environment and into people’s bodies, the nonprofit group began calling for a ban on all non-medical uses of triclosan.

“Triclosan targets the thyroid system of humans and wildlife,” said Sonya Lunder, senior analyst with the group. “The potential for human harm is high, and there’s a real concern for the aquatic environment. The benefits of triclosan are minimal, if any.”

She and others noted that Johnson & Johnson announced in 2012 that it would stop using triclosan in its products. This year, Proctor & Gamble followed suit, pledging to phase it out by 2014.

Also this year, Minnesota became the first state to ban purchases of triclosan-containing products by state agencies. The action came in response to a University of Minnesota study that found the dioxin-like breakdown products of triclosan in sediments of lakes that receive treated wastewater, along with studies linking it to antibiotic resistance and endocrine disruption.

As the concerns mount, the Personal Care Products Council is resisting calls to ban or curtail the use of triclosan. A request for comment from the group, which represents health and beauty products companies, was directed to a sister organization, the American Cleaning Institute. That group acknowledged The Day’s request but did not comment.

The Personal Care Products Council articulated its position on triclosan in a 2010 statement to the FDA and in a 2011 announcement, both on its website. It argued that triclosan-containing products are effective and critical in reducing people’s risk of disease and cited a 2011 study in the International Journal of Microbiology Research showing no increase in the presence of antibiotic-resistant staphylococcus bacteria in users of antibacterial hand soaps compared to non-users. The research was supported by the council and the cleaning institute.

“After decades of use, antibacterial wash products continue to play a beneficial role in everyday hygiene routines for millions of people around the world,” Francis Kruszewski, director of human health and safety at the cleaning institute, said in the statement.

Consequences of choices

At the EPA, research into triclosan and other emerging contaminants continues, but it’s expensive and highly complicated, said Katrina Kipp, manager of the ecosystems assessment unit at the agency’s New England office.

“There isn’t yet a regulatory framework for controlling emerging contaminants, and states don’t have the water quality criteria they need,” she said. To regulate these chemicals, researchers would have to figure out what levels are harmful, among many other questions. Still, there is ample published research showing that exposure to some of these contaminants causes male fish to develop female characteristics, results in changes in fish behavior and affects thyroids in frogs, among other findings, so there clearly is a need for more studies, she said.

“Even at very low levels, there have been effects,” Kipp said.

In Connecticut, the state Department of Energy and Environmental Protection is aware of the emerging contaminants issue but doesn’t appear ready to recommend actions such as those taken in Minnesota. The state Department of Administrative Services, which sets supply purchase policies for state agencies, did not respond to a request for comment about products containing triclosan.

“At this point, we are following the science and analyzing all available data, but we do not yet have enough information to recommend any specific regulatory action,” DEEP spokesman Dennis Schain said. “This issue does point to the fact that choices we all make as consumers can have consequences for our environment, and people should try to make informed decisions about the products they purchase.”

Traci Iott, supervising environmental analyst at DEEP, said her agency is using public education to try to keep pharmaceuticals and personal care products from being flushed down the drain and to encourage people to bring unused products to community collection events.

While scientists and regulators continue to work on the emerging contaminants problem, MacKay sees a larger lesson for the public. People can become aware that their choices about products affect the larger environment, she said. They can decide not to use products with triclosan, and they can be more careful with their pharmaceuticals. And, if these compounds are able to survive the sewage treatment process, how much greater are the effects of chemicals people carelessly spill or dump directly into waterways?

“This is a rather indirect pathway to the environment,” she said, “and I would hope that people might be more conscious in their decisions about products that would have more direct pathways, like lawn care products and things you use working on your car.”

Source: The Day

Pure Water Gazette Fair Use Statement

the month, according to data from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

the month, according to data from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

![carbonpores1[1]](http://www.purewatergazette.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/carbonpores11.jpg)