A Thirsty, Violent World

by Michael Specter

Angry protesters filled the streets of Karachi last week, clogging traffic lanes and public squares until police and paratroopers were forced to intervene. That’s not rare in Pakistan, which is often a site of political and religious violence.

But last week’s protests had nothing to do with freedom of expression, drone wars, or Americans. They were about access to water. When Khawaja Muhammad Asif, the Minister of Defense, Power, and Water (yes, that is one ministry), warned that the country’s chronic water shortages could soon become uncontrollable, he was looking on the bright side. The meagre allotment of water available to each Pakistani is a third of what it was in 1950. As the country’s population rises, that amount is falling fast.

Dozens of other countries face similar situations—not someday, or soon, but now. Rapid climate change, population growth, and a growing demand for meat (and, thus, for the water required to grow feed for livestock) have propelled them into a state of emergency. Millions of words have been written, and scores of urgent meetings have been held, since I last wrote about this issue for the magazine, nearly a decade ago; in that time, things have only grown worse.

The various physical calamities that confront the world are hard to separate, but growing hunger and the struggle to find clean water for billions of people are clearly connected. Each problem fuels others, particularly in the developing world—where the harshest impact of natural catastrophes has always been felt. Yet the water crisis challenges even the richest among us.

California is now in its fourth year of drought, staggering through its worst dry spell in twelve hundred years; farmers have sold their herds, and some have abandoned crops. Cities have begun rationing water. According to the London-based organization Wateraid, water shortages are responsible for more deaths in Nigeria than Boko Haram; there are places in India where hospitals have trouble finding the water required to sterilize surgical tools.

Nowhere, however, is the situation more acute than in Brazil, particularly for the twenty million residents of São Paulo. “You have all the elements for a perfect storm, except that we don’t have water,” a former environmental minister told Lizzie O’Leary, in a recent interview for the syndicated radio show “Marketplace.” The country is bracing for riots. “There is a real risk of social convulsion,” José Galizia Tundisi, a hydrologist with the Brazilian Academy of Sciences, warned in a press conference last week. He said that officials have failed to act with appropriate urgency. “Authorities need to act immediately to avoid the worst.” But people rarely act until the crisis is directly affecting them, and at that point it will be too late.

It is not that we are actually running out of water, because water never technically disappears. When it leaves one place, it goes somewhere else, and the amount of freshwater on earth has not changed significantly for millions of years. But the number of people on the planet has grown exponentially; in just the past century, the population has tripled, and water use has grown sixfold. More than that, we have polluted much of what remains readily available—and climate change has made it significantly more difficult to plan for floods and droughts.

Success is part of the problem, just as it is with the pollution caused by our industrial growth. The standard of living has improved for hundreds of millions of people, and the pace of improvement will quicken. As populations grow more prosperous, vegetarian life styles often yield to a Western diet, with all the disasters that implies. The new middle classes, particularly in India and China, eat more protein than they once did, and that, again, requires more water use. (On average, hundreds of gallons of water are required to produce a single hamburger.)

Feeding a planet with nine billion residents will require at least fifty per cent more water in 2050 than we use today. It is hard to see where that water will come from. Half of the planet already lives in urban areas, and that number will increase along with the pressure to supply clean water.

“Unfortunately, the world has not really woken up to the reality of what we are going to face, in terms of the crises, as far as water is concerned,” Rajendra Pachauri, the chairman of the International Panel on Climate Change, said at a conference on water security earlier this month. “If you look at agricultural products, if you look at animal protein, the demand for which is growing—that’s highly water intensive. At the same time, on the supply side, there are going to be several constraints. Firstly because there are going to be profound changes in the water cycle due to climate change.”

Floods will become more common, and so will droughts, according to most assessments of the warming earth. “The twenty-first-century projections make the [previous] mega-droughts seem like quaint walks through the garden of Eden,” Jason Smerdon, a climate scientist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, said recently. At the same time, demands for economic growth in India and other developing nations will necessarily increase pollution of rivers and lakes. That will force people to dig deeper than ever before into the earth for water.

There are ways to replace oil, gas, and coal, though we won’t do that unless economic necessity demands it. But there isn’t a tidy and synthetic invention to replace water. Conservation would help immensely, as would a more rational use of agricultural land—irrigation today consumes seventy per cent of all freshwater.

The result of continued inaction is clear. Development experts, who rarely agree on much, all agree that water wars are on the horizon. That would be nothing new for humanity. After all, the word “rivals” has its roots in battles over water—coming from the Latin, rivalis, for “one taking from the same stream as another.” It would be nice to think that, with our complete knowledge of the physical world, we have moved beyond the limitations our ancestors faced two thousand years ago. But the truth is otherwise; rivals we remain, and the evidence suggests that, until we start dying of thirst, we will stay that way.

Source: The New Yorker.

Pure Water Gazette Fair Use Statement

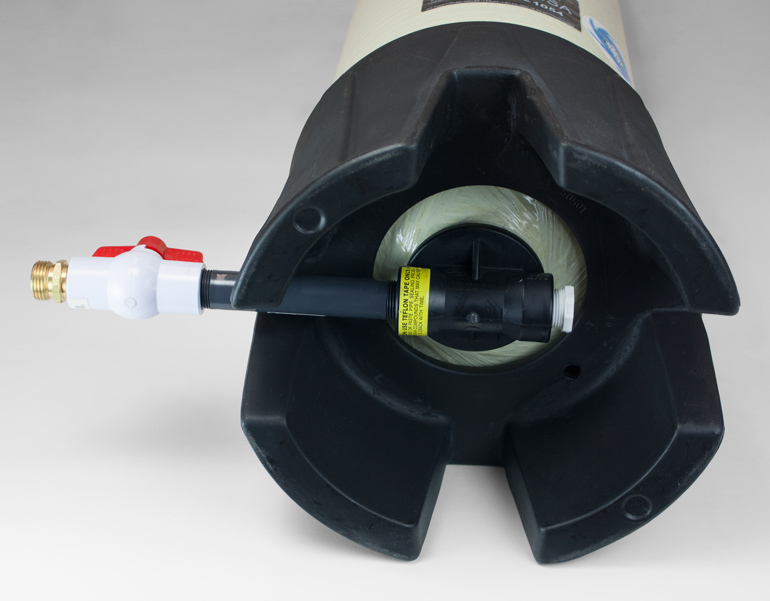

Our new AerMax installation kit mounts the air pump on the tank itself.

Our new AerMax installation kit mounts the air pump on the tank itself.

![rc400[1]](http://www.purewatergazette.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/rc4001-169x300.jpg)

![pwanniemedium[1]](http://www.purewatergazette.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/pwanniemedium1-246x300.jpg)