Has your water been tested for perfluorooctanoic acid? Probably Not,

Below are the opening lines of an article from the Hoosick Falls, NY Times Union:

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issued a statement in November 2015 warning residents in Hoosick Falls not to drink or cook with village water because of elevated levels of a toxic chemical found in the public water system last year.

In response, the village’s mayor has reversed his position, and adopted the EPA’s recommendation.

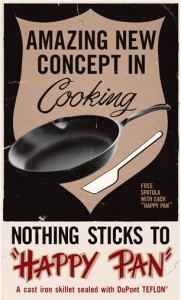

The man-made chemical, perfluorooctanoic acid, or “PFOA,” was used since the 1940s to manufacture industrial and household products such as non-stick coatings and heat-resistant wiring, including at a factory near the village water treatment plant. The chemical was discovered in the village water system last year by a private citizen, Michael Hickey, whose father, John, died of kidney cancer in 2013. PFOA has been linked to kidney and testicular cancer, as well as thyroid diseases and other serious health problems.

The EPA’s public statement was issued four days after a Times Union story reported that the state Health Department and village leaders, including Mayor David B. Borge, downplayed the health risks of PFOA in the water supply, and declined to warn people not to drink it. The story reported that many village residents, including a longtime family physician in Hoosick Falls, Dr. Marcus E. Martinez, suspected that high cancer rates and other extraordinary health problems in the village’s population may be the result of the contaminated water.

“While the EPA continues to gather information and assess the Hoosick Falls water contamination, it recommends that people not drink the water from the Hoosick Falls public water supply or use it for cooking,” the EPA’s statement said. The agency’s statement said it does not believe that showering or bathing in the water poses a risk for unsafe exposure to PFOA.

Perfluorinated Chemicals (PFCs) are a group of manufactured chemicals used in a wide range of industries and commercial products. The two most common PFCs are perfluorooctanoic acid (also known as PFOA or C8) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS). PFCs have been in use since the 1940s to make products that are water-, oil-, fire-, stain- or grease-resistant—products like Teflon®, non-stick cookware, stain-resistant carpeting and fire-extinguishing foams.

PFCs are among a group of chemicals that the EPA has labelled “emerging contaminants”—chemicals that may pose or are percieved to pose a threat to human health or the environment. PFCs are of concern because:

- They break down slowly in the environment and move about readily in air.

- They have been detected in surface water in cities throughout the U.S.

- They have been detected in the blood of as many as 98% of Americans.

- Once in the body they tend to stay there for a long period of time, about 4 years.

- They have been shown to cause developmental and other health effects in laboratory animals.

In the late 1990s it was discovered that PFOS was present in the blood of a vast majority of the American population. The EPA met with 3M, the primary manufacturer, who agreed to phase out manufacturing of the chemical and to cease production by the year 2002. PFOA underwent a similar phase-out through an EPA “Stewardship Program” of major manufacturers that should see most emissions and use reduced significantly by the year 2015.

Human exposure may occur through diet, inhalation, or use of products containing the chemicals. The EPA reports that “fish and fishery products” appear to be a primary source.

As the Hoosick Falls article indicates, C8 and PFOA can also enter your body through drinking contaminated water.

The revelation that PFOA has long contaminated the water of Hoosick Falls clearly indicates that chemicals may be in water supplies without the knowledge of those who drink the water. PFOQ is one of literally hundreds of thousands of unregulated chemicals that are in use throughout the country.

It only makes sense to protect yourself with a point of use water filtration system whether or not there is evidence of chemical contamination.

The EPA, by the way, recommends carbon filtration or reverse osmosis as the best home treatments for PFOA.

Read the full Hoosick Falls report in the Times Union.

More about PFCs on the Pure Water Products contaminants page.