PH Paranoia: Understanding Alkaline Water Claims

The unique properties of mineral free, ultra-pure drinking water actually makes pH measurement meaningless in the body.

by Jack Barber

It’s an all-too-common misconception that alkaline water is the key to perfect health even though claims about the health benefits, or safety, of this water are not supported by much credible evidence. Clever marketers rely on personal testimonials and pseudo-scientific studies to promote alkaline water as a powerful antioxidant that can prevent or reverse many degenerative diseases, including cancer and arthritis, boost energy levels and metabolism and slow the aging process. There is absolutely no scientific proof that any of these claims are true.

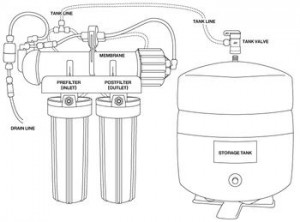

In the war of the waters, alkaline water zealots not only shamelessly promote the benefits of alkaline water but take shots at both distillation (D) and reverse osmosis (RO). They believe that drinking DRO water is actually harmful because it can be slightly acidic. The truth is the unique properties of mineral free, ultra-pure drinking waters actually make the pH measurement meaningless in the body. It is important to note that de-ionized, rain and many spring waters also have the same properties that make them acidic.

Explanation of pH and why it matters

To better understand how the body renders this debate meaningless, it is necessary to have a basic explanation of pH. The pH level is a quantitative measure of the hydrogen ions representing the acidity or alkalinity of a solution. The acidic solution has more free hydrogen ions and the alkaline solution has fewer free hydrogen ions. Any substance that lowers pH is an acid and any substance that raises it is a base. Buffers are substances that enable water to resist pH change when an acid or base is added.

The pH scale ranges from 0 to 14 with a pH of 7 being neutral. A pH less than 7 is acidic and a pH greater than 7 is alkaline. The pH scale is logarithmic so for every one unit of change in pH there is a tenfold change in ion concentration. This means a solution with a pH of 3 is 10 times more acidic than a solution with a pH of 4 and 100 times more acidic than one with a pH of 5.

The effects on the pH scale from drinking DRO water

Highly purified DRO water is neutral with a pH of 7. Since there are virtually no dissolved solids (TDS) in this water, there is nothing to influence the pH change in either the alkaline or acid direction or to act as buffers to resist change. That degree of purity makes DRO water extremely sensitive so adding the slightest amount of acid or base will easily change the pH. Even a small amount of carbon dioxide from the air will combine with DRO water to lower the pH to about 6. For the same reason, just a speck of an alkalizing substance like baking soda will immediately raise the pH of a glass to over 7. In contrast, it would require considerably more acid or base to change the pH of mineral water. The difference is the presence of buffers or dissolved solids making it resistant to change. In other words, the pH of DRO water is like a pendulum that can be moved easily with a feather compared to high mineral water that requires a mallet.

Therefore, when you drink slightly acidic DRO water, it immediately combines with the slightly acidic digestive enzymes in saliva and seconds later with very acidic digestive enzymes and gastric juices in the stomach without affecting your pH in any way. In short, the extremely sensitive DRO water pH immediately adjusts to your body rather than your body adjusting to the DRO water pH. The much stronger hydrochloric acid in the stomach with a pH of 1 is about 100,000 times more acidic than any slightly acidic DRO water with which it combines. That renders the pH of DRO water completely irrelevant.

Reasons not to drink alkaline water

According to Dr. Bob Arnot, M.D., who is a well-known author and nutritionist, in a recent Men’s Health Journalarticle, “Say no to alkaline water, it’s a scam. Your body is designed to adjust to its optimal pH balance no matter what you ingest. For instance, once alkaline water enters your stomach, your body simply pours in greater amounts of acid to neutralize it.”

Since the stomach is designed to be acidic, it must produce more acid every time you drink alkaline water to compensate for the dilution of gastric juices. In a previously healthy gut, the constant ingestion of alkalized water can create an abnormal digestive condition. Even drinking alkalized water along with meals can dilute the natural acidity of the digestive tract and interfere with digestion.

Maintaining normal stomach acidity is also necessary to protect against bacterial and viral infections. The acidic environment destroys pathogenic organisms that may be ingested in both food and water. Altering this acid environment leaves you wide open to intestinal infections. At least half of everyone over 60 suffers from some level of low stomach acid. This condition can be compounded by the consumption of alkaline water.

As a Harvard Medical School graduate, nationally known author and nutritionist Dr. Andrew Weil is eminently qualified to evaluate the health claims of alkaline water. He said, “The health claims for water ionizers and alkaline water are bogus. Save your money. You should consider the fact that alkaline water is common throughout the western states, but to my knowledge, it has not protected anyone from the diseases and disorders that occur elsewhere in the U.S.”

Nutritionist and pure water advocate Dr. A. True Ott noted, “Water that is rich in hydrogen measures 5 or 6 on the pH scale (acidic), while alkaline water is actually dehydrating. In my experimentation and research, there is a direct correlation with water purity levels and hydrogen content. Thus, one should strive to consume the purest water possible, water rich in free hydrogen ions. Why then are people often tricked into thinking that drinking water with high TDS contaminants such as ionized water is actually a wise and healthy thing to do? Science and logic scream otherwise.”

Don’t fall for the easy way out

In spite of all the warnings, most people want the best health without the sacrifices needed to achieve it safely. We all love the idea of a quick fix. What better way to correct years of poor nutrition, zero exercise and chronic dehydration than by simply drinking alkaline water? Savvy marketers prey on these consumers, selling useless products that may cause severe long-term side effects. Using nothing more than sales fiction, they have beguiled trusting consumers and created a thriving market for expensive alkalizing gizmos known as ionizers.

These popular ionizers, according to scientists, are not only medically baseless and worthless, but also possibly dangerous. Four Japanese studies have been published in peer journals and independently verified showing that alkaline water caused pathological changes in heart cell muscles and increased the risk of heart attack in laboratory animals.

Normal cells die under extremely alkaline conditions. A study published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry found that alkalosis (rising cellular pH) causes alkaline-induced cell death as a result of altering mitochondrial function. These results raise very serious doubts about the safety of alkaline water.

Dr. David Brownstein, author, international lecturer and foremost practitioner of holistic medicine, said, “I disagree with the claims made about alkaline water. The claims about the benefits of drinking alkaline are made with no supporting evidence. The best way to optimize your pH is to eat a healthy diet full of minerals and vitamins. Eating refined foods like white flour, sugar and salt promote acidity.”

The wide range of pH values needed throughout the body is exquisitely balanced, primarily through a complex system of buffering and breathing. There are, however, some simple things you can do to maintain a naturally healthy pH. Eating more fruits and vegetables, practicing deep breathing and drinking plenty of pure hydrating water will enable your body to more easily remove toxins and acid metabolic wastes.

Other factors, such as lack of exercise, emotional stress, medication, coffee, alcohol and smoking, can adversely affect the internal pH of your body over an extended period of time. Thus, improved health is not a quick-fix but a slow, cumulative process consisting of numerous lifestyle choices.

It is my sincere hope that this combination of scientific studies, expert advice and common horse sense settles the pH debate so we can all freely enjoy the pure, oxygen-rich elixir of life without any pH paranoia.

Source: Water Technology.

Pure Water Gazette Fair Use Statement

Q