Not All In-Home Drinking Water Filters Completely Remove Toxic PFAS

Research by Duke and NC State scientists finds most filters are only partially effective at removing PFAS. A few, if not properly maintained, can even make the situation worse.

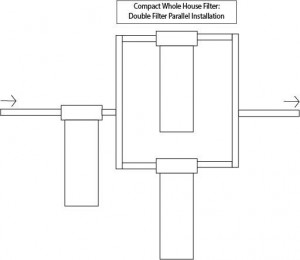

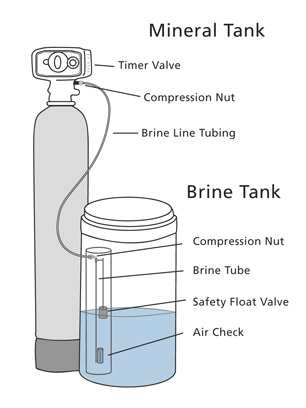

Pure Water Gazette introductory note. We’re reprinting WaterOnline’s reporting on Duke University research that appeared recently. We take issue with the “glass is half empty” title, which more appropriately should be “All Home Reverse Osmosis Units Tested In Duke Research Removed PFAS Handily.” Are we supposed to be surprised and disappointed that a $35 end-of-faucet filter from Walmart failed to remove tiny amounts of perfluoroalkyl sulfonic acids, perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids, and per- and poly-fluoroalkyl ether acids from tap water? We take issue as well with the implication that home reverse osmosis units are luxury items beyond the reach of homeowners because of cost. A home appliance that costs less than a smart phone and provides years of superb drinking water? We added the image below from the original Duke research because it summarizes the findings: small carbon filters were partially effective, double undersink filters were very effective (though researchers could not explain why), and undersink reverse osmosis units of various brands, states of upkeep and age were uniformly effective.

The water filter on your refrigerator door, the pitcher-style filter you keep inside the fridge and the whole-house filtration system you installed last year may function differently and have vastly different price tags, but they have one thing in common.

They may not remove all of the drinking water contaminants you’re most concerned about.

A new study by scientists at Duke University and North Carolina State University finds that – while using any filter is better than using none – many household filters are only partially effective at removing toxic perfluoroalkyl substances, commonly known as PFAS, from drinking water. A few, if not properly maintained, can even make the situation worse.

“We tested 76 point-of-use filters and 13 point-of-entry or whole-house systems and found their effectiveness varied widely,” said Heather Stapleton, the Dan and Bunny Gabel Associate Professor of Environmental Health at Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment.

“All of the under-sink reverse osmosis and two-stage filters achieved near-complete removal of the PFAS chemicals we were testing for,” Stapleton said. “In contrast, the effectiveness of activated-carbon filters used in many pitcher, countertop, refrigerator and faucet-mounted styles was inconsistent and unpredictable. The whole-house systems were also widely variable and in some cases actually increased PFAS levels in the water.”

“Home filters are really only a stopgap,” said Detlef Knappe, the S. James Ellen Distinguished Professor of Civil, Construction and Environmental Engineering at NC State, whose lab teamed with Stapleton’s to conduct the study. “The real goal should be control of PFAS contaminants at their source.”

PFAS have come under scrutiny in recent years due to their potential health impacts and widespread presence in the environment, especially drinking water. Exposure to the chemicals, used widely in fire-fighting foams and stain- and water-repellants, is associated with various cancers, low birth weight in babies, thyroid disease, impaired immune function and other health disorders. Mothers and young children may be most vulnerable to the chemicals, which can affect reproductive and developmental health.

Some scientists call PFAS “forever chemicals” because they persist in the environment indefinitely and accumulate in the human body. They are now nearly ubiquitous in human blood serum samples, Stapleton noted.

The researchers published their peer-reviewed findings Feb. 5 [2020] in Environmental Science & Technology Letters. It’s the first study to examine the PFAS-removal efficiencies of point-of-use filters in a residential setting.

They analyzed filtered water samples from homes in Chatham, Orange, Durham and Wake counties in central North Carolina and New Hanover and Brunswick counties in southeastern N.C. Samples were tested for a suite of PFAS contaminants, including three perfluoroalkal sulfonic acids (PFSAs), seven perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs) and six per- and poly-fluoroalkyl ether acids (PFEAs). GenX, which has been found in high levels in water in the Wilmington area of southeastern N.C., was among the PFEAs for which they tested.

Key takeaways include:

- Reverse osmosis filters and two-stage filters reduced PFAS levels, including GenX, by 94% or more in water, though the small number of two-stage filters tested necessitates further testing to determine why they performed so well.

- Activated-carbon filters removed 73% of PFAS contaminants, on average, but results varied greatly. In some cases, the chemicals were completely removed; in other cases they were not reduced at all. Researchers saw no clear trends between removal efficiency and filter brand, age or source water chemical levels. Changing out filters regularly is probably a very good idea, nonetheless, researchers said.

- The PFAS-removal efficiency of whole-house systems using activated carbon filters varied widely. In four of the six systems tested, PFSA and PFCA levels actually increased after filtration. Because the systems remove disinfectants used in city water treatment, they can also leave home pipes susceptible to bacterial growth.

“The under-sink reverse osmosis filter is the most efficient system for removing both the PFAS contaminants prevalent in central N.C. and the PFEAs, including GenX, found in Wilmington,” Knappe said. “Unfortunately, they also cost much more than other point-of-use filters. This raises concerns about environmental justice, since PFAS pollution affects more households that struggle financially than those that do not struggle.”

Nick Herkert, a postdoctoral associate in Stapleton’s lab, was lead author on the study. John Merrill of NC State and Cara Peters, David Bollinger, Sharon Zhang, Kate Hoffman and Lee Ferguson of Duke were co-authors. Funding came from the N.C. Policy Collaboratory through the N.C. PFAS Testing Network and from the Wallace Genetic Foundation. Duke and NC State scientists finds most filters are only partially effective at removing PFAS. A few, if not properly maintained, can even make the situation worse.

Source: WaterOnline.