Water News for May, 2023

Home of the EPA in Washington, DC

Certainly the biggest water news of the month was the breakthrough agreement of water managers in Arizona, California and Nevada to cut back water use from the Colorado River to keep the river from falling to a level that could endanger the water supply of farms and cities that depend on the river. The federal government will pay some $1.2 billion dollars to cities, irrigation districts and Native American tribes if they temporarily use less water. National Public Radio.

The US Environmental Protection Agency is taking unprecedented enforcement action over PFAS water pollution by ordering the chemical giant Chemours’ Parkersburg, West Virginia, plant to stop discharging extremely high levels of toxic PFAS waste into the Ohio River. The river is a drinking water source for 5 million people, and the EPA’s Clean Water Act violation order cites 71 instances between September 2018 to March 2023 in which Chemours’ Washington Works facility discharged more PFAS waste than its pollution permit allowed.

The agency also noted damaged facilities and equipment that appeared to be leaking PFAS waste onto the ground. The chemicals are ubiquitous and linked at low levels of exposure to cancer, thyroid disease, kidney dysfunction, birth defects, autoimmune disease and other serious health problems. The step by the EPA drew praise from some environmental groups, but at least one noted the permit still allows high levels of PFAS pollution and may not adequately protect the environment and human health. The Guardian.

The action against Chemours is notable for being the first EPA Clean Water Act enforcement action ever taken to hold polluters accountable for discharging PFAS into the environment. PFAS pollution has been going on for decades and this is the EPA’s first action again polluters.

Five leading water associations — the American Water Works Association (AWWA), Association of Metropolitan Water Agencies (AMWA), National Association of Clean Water Agencies (NACWA), National Association of Water Companies (NAWC), and Water Environment Federation (WEF) — have submitted formal policy recommendations to Congress and the White House on establishing a permanent federal low-income household water assistance program (LIHWAP), according to an AMWA press release.

As part of their recommendations, the groups released also released a detailed analysis, “Low-Income Water Customer Assistance Program Assessment Study,” which establishes that water affordability is a significant challenge for 20 million U.S. households and puts the annual need for federal funding to address this challenge as high as $7.9 billion.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced $2,499,579 in research grant funding to Texas Tech University for research on the behavior of perchlorate after fireworks events near water sources.

“Protecting our water resources and ensuring clean drinking water is one of EPA’s top priorities,” said Chris Frey, Assistant Administrator of EPA’s Office of Research and Development. “With this research grant, Texas Tech University will be able to provide states and utilities with further knowledge on how to protect drinking water from perchlorate contamination.”

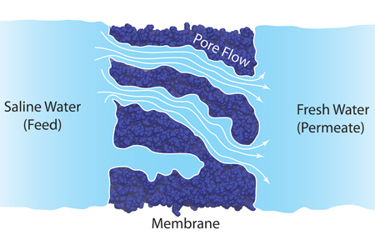

Perchlorate is a chemical used in rocket propellants, explosives, flares and fireworks. Recent increases in the use of fireworks have caused concern over potential increases of perchlorate in ambient waters that serve as sources of drinking water. Perchlorate in drinking water sources can be a health concern because above certain exposure levels, perchlorate can interfere with the normal functioning of the thyroid gland. Prior research has investigated water contamination from fireworks; however, there are gaps in understanding the magnitude and extent of perchlorate contamination before, during, and after fireworks are discharged around drinking water sources. (The best way to remove perchlorate from drinking water is reverse osmosis.)

Racial and ethnic divide in concerns about drinking water quality

An ongoing national poll has found that most adults in the country are significantly worried about contaminated drinking water — results that are notably higher for minority consumers.

“Over the past two decades, Gallup has consistently found that Americans worry more about pollution of drinking water than other environmental concerns,” Gallup reported. “In response to Gallup’s annual environmental polls from 2019 to 2023, 56% of Americans overall said they worry ‘a great deal’ about pollution of drinking water. However, that sentiment was expressed by 76% of Black adults and 70% of Hispanic adults, compared with less than half (48%) of White adults.”

Across all adults polled, 56% indicated that they worry about pollution of drinking water “a great deal” and 24% indicated that they worry about it “a fair amount.”

Gallup attributed the racial disparity to the prevalence of major drinking water contamination emergencies in communities of color, like Flint, Michigan and Jackson, Mississippi.

“Racial and ethnic differences in concern about drinking water likely stem from a mixture of direct experience and media coverage of disasters that have disproportionately affected minority communities,” according to Gallup. “Many low-income Black and Hispanic Americans live in areas with aging infrastructure … Black and Hispanic Americans’ greater likelihood to worry about tainted water suggests a lack of faith in regulators to keep the public safe in light of crises like those in Flint and other cities with large communities of color.”

Indeed, communities of color are disproportionately impacted by drinking water contamination issues, giving them good reason to feel concerned about it. Another recent study found they are more likely to consume one of the most high-profile classes of contaminants than others.

“Residents of communities with bigger Black and Hispanic populations are more likely to be exposed to harmful levels of ‘forever chemicals’ in their water supplies, a new study has found,” per The Hill. “This increased risk of exposure is the result of the disproportionate placement of pollution sources near watersheds that serve these communities.”

As these communities face significant drinking water quality issues and their concerns about these issues grow, water system operators and regulators clearly have a long road ahead in establishing more public trust.

Research reported in The Guardian indicates that by the end of the century up to 70% of California’s beaches could be gone.