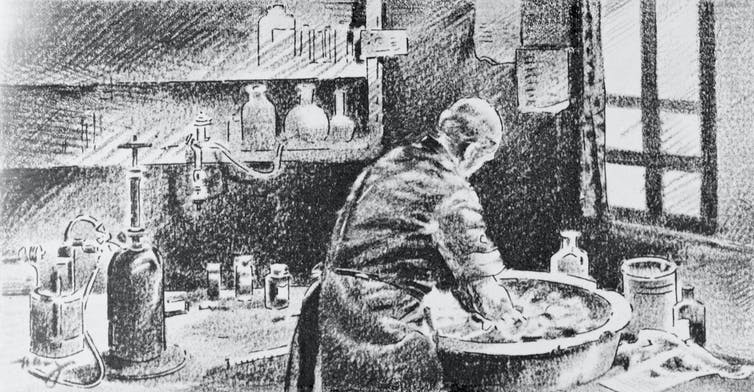

Gazette’s Famous Water Pictures: Dr. Semmelweis Washing His Hands

Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis washing his hands in chlorinated lime water before attending to patients.

History of Hand-Washing

The idea that “germs” that cause disease get on people’s hands and that they can be spread from person to person by unclean hands hasn’t been around that long. In fact, it was 19th-century Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis who, after observational studies, first advanced the idea of “hand hygiene” in medical settings. Here’s how Semmelweis, working in an obstetrics ward in Vienna in the 19th century, made the connection between dirty hands and deadly infection.

Hand-Washing in the old days

While we certainly don’t know the name of the first guy to wash his hands, the history of hand-washing extends back to ancient times, when it was largely a religious practice. The Old Testament, the Talmud and the Quran all mention hand-washing in the context of ritual cleanliness, and it may be that ritual hand washing had some public health implications. During the Black Death of the 14th century, for instance, the Jews of Europe had a distinctly lower rate of death than others. Researchers believe that hand-washing prescribed by their religion probably served as protection during the epidemic.

Dr. Semmelweis

Hand-washing as a health care practice did not really surface until the mid-1800s, when a young Hungarian physician named Ignaz Semmelweis did an important observational study at Vienna General Hospital.

Semmelweis started working in obstetrics, a relatively new and not very prestigious area for physicians, in the Vienna Hospital in 1846. Obstetrics had to that time been dominated by midwifery and conventional doctors were trying to expand into the childbirth business.

The leading cause of maternal mortality in Europe at that time was puerperal fever–an infection, now thought to be caused by the streptococcus bacterium, that killed postpartum women. Prior to 1823, about 1 in 100 women died in childbirth at the Vienna Hospital. But after a policy change mandated that medical students and obstetricians perform autopsies in addition to their other duties, the mortality rate for new mothers suddenly jumped to 7.5%.

When the hospital opened a second obstetrics division, staffed entirely by midwives, the older division, where Dr. Semmelweis worked, was quickly seen to have a much higher mortality rate than the new midwives’ division.

Semmelweis set out to investigate. He examined all the similarities and differences of the two divisions. The only significant difference was that male doctors and medical students worked in the first division and female midwives in the second.

What transmits disease?

At that time, the general belief was that bad odors called “miasma” transmitted disease. It would be two more decades at least before germ theory–the idea that microbes cause disease–took over as the accepted theory, the theory that persists until today.

Semmelweis reasoned that no midwives ever participated in autopsies or dissections, but students and physicians regularly went between autopsies and deliveries, rarely washing their hands in between. Realizing that chloride solution rid objects of their odors, Semmelweis ordered hand-washing across his department. Starting in May 1847, anyone entering the doctors’ obstetrical division had to wash his hands in a bowl of chloride solution. The incidence of puerperal fever and death dropped sharply by the end of the year.

Unfortunately, as in the case of his contemporary John Snow, who discovered that cholera was transmitted by polluted water and not miasma, Semmelweis’ work did not get him a place in history or even a promotion. In fact, he lost his job because his boss was envious of his success and got no recognition for the discovery during his lifetime.

Hand-washing has now, of course, become a part of the medical ritual, but it gets a definite bump of compliance whenever there is disease outbreak. Even in times of pandemic, though, we do not have a day on our calendar that honors Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis. There is no justice.

Adapted using information drawn from The Conversation.