How to Be Eco-Friendly When You’re Dead

by Shannon Palus

Gazette Introductory Note: We’ve visited the issue of body disposal and water quality before. See, for example, “How the dead pollute water.” Also, “Formaldehyde as a Water Contaminant.” Clearly both burial and cremation have advantages and disadvantages. The Atlantic article below examines the options in greater detail and introduces such concepts as “green cremation.” –Hardly Waite.

When Phil Olson was 20, he earned money in the family business by draining the blood from corpses. Using a long metal instrument, he sucked the fluid out of the organs, and pumped the empty space and the arteries full of three gallons of toxic embalming fluid. This process drains the corpse of nutrients and prevents it from being eaten by bacteria, at least until it’s put into the ground. Feebly encased in a few pounds of metal and wood, it wasn’t long until all the fluid and guts just leak back out.

Most of the bodies Olson prepared in his family’s funeral home would then be buried in traditional cemeteries, below a lawn of grass that must be mowed, watered, sprayed with pesticides, and used for nothing else, theoretically until the end of time.

Cemeteries “are kind of like landfills for dead bodies,” says Olson. Today, as a philosopher at Virginia Tech, his work looks at the alternatives to traditional funeral practices. He has a lot to think about: The environmentally friendly funeral industry is booming, as people begin to consider the impacts their bodies might have once they’re dead. Each year, a million pounds of metal, wood, and concrete are put in the ground to shield dead bodies from the dirt that surrounds them. A single cremation requires about two SUV tanks worth of fuel. As people become increasingly concerned with the environment, many of them are starting to seek out ways to minimize the impact their body has once they’re done using it.

There all kinds of green practices and products available these days on the so-called “death care” market. So many, in fact, that in 2005 Joe Sehee founded the Green Burial Council—a non-profit that keeps tabs on the green funeral industry, offering certifications for products and cemeteries. Sehee saw a need to prevent meaningless greenwashing in the green burial world. “It is a social movement. It’s also a business opportunity,” he said. So what’s the most environmentally friendly way to dispose of a body? It all depends on your preferences.

For those who still want to be be buried, a greener approach may include switching out the standard embalming fluids made of a combination of formaldehyde and rubbing alcohol, with ones made of essential oils. And instead of a heavy wood and metal box that will take years to degrade and leave behind toxic residue, there are now Green Burial Council-certified biodegradable cedar caskets.

Others are choosing to forgo the casket completely and opt for what’s called a “natural burial,” involving only a burlap sack buried in the woods. If you don’t have a forest handy, in some cities bodies may soon be placed in an industrial sized compost bin, and turned over to create fertile soil.

That’s the idea behind the Urban Death Project, which envisions a three-story downtown cemetery for bodies: a stylized pit of sorts, filled with carbon-rich material. Microbes decompose the bodies into a compost. It is a green practice, but not simply a utilitarian one: Urban Death Project bills itself as “a space for contemplation of our place in the natural world.” Bodies are “folded back into the communities where they have lived,” the website explains.

For those who might have opted for cremation rather than burial, there are green alternatives to that as well. Currently on the market is a method called “green cremation” that uses a pressurized metal chamber and bath of chemicals. The technique started out as a way to dispose of lab animals at Albany Medical College, and it is now legal for use on humans in just eight states.

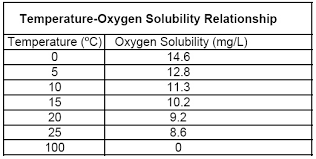

In this method, also known as alkaline hydrolysis, bodies are dissolved into a liquid that is safe to flush into the sewage system. Overall, the process uses 90 percent less energy than traditional cremation—though it will skyrocket a funeral home’s water bills. “It uses a ton, a ton, of water,” says Olson. According to an alkaline hydrolysis system manufacturer, about 300 gallons per human body. Olson thinks recycled “grey water” could be used to cut down on the water waste. But he wonders: “Will families say, ‘I don’t want grandma dissolved in dirty dishwater’?”

Olson says that it’s not necessarily the green-ness of this new cremation that appeals to people. It’s how gentle it seems. “Burning grandma in fire seems to be violent,” he says. “In contrast, green cremation is ‘putting grandma in a warm bath.’”

And that perception is generally far more important to people than the eco-friendliness of the process. Even projects that put the environment front-and-center emphasize the feeling of a pleasant exit, and a lasting connection to the Earth.

So what does Sehee look for in a truly green burial? Something that works to actively conserve rural land. The council awards three leaves—the highest rating available—to burial plots that not only eschew embalming fluid and vaults, but double as conservation spaces. A three-leaved process does away with nearly every environmental concern related to burial and cremation and works to keep land free of development and pesticide.

Ultimately, which eco-friendly exit you choose is mostly about personal comfort. And if the choices seem daunting, it’s worth remembering: Even the most energy-intensive acts of burial pale in comparison to the carbon footprint you’re leaving right now.

Source: The Atlantic.