A Relentless Drought Is Forcing Las Vegas to Take Extreme Measures

by Arnie Cooper

Editor’s Note. The dire water shortage facing Las Vegas is hardly news, but this Newsweek piece does a fine job of providing perspective. Drought isn’t new to the area, but drought plus overpopulation plus increasing temperatures have created a much more complicated scenario than that faced by the Anasazi who lived in the area a thousand years ago. The article below offers a particularly good overview of the problem and possible solutions. — Hardly Waite.

The Colorado

When a 60-year drought slowed the mighty Colorado back in the 12th century, it didn’t much matter. The river had to feed only local wildlife and not the millions of people who have since settled in sprawling and hugely water-dependent metropolises like Las Vegas.

Today another dry spell is blistering much of the Southwest. Of course, no one can say whether this 14-year-event will become a decades-long megadrought, but the city is taking no chances. Counter to its reputation, Las Vegas has been one of the country’s most progressive municipalities when it comes to water conservation. Despite explosive population growth, per capita water use has dropped 40 percent in the past two decades, water recycling is up, and homeowners are pulling up their sod in record numbers to save H2O.

But it’s still not enough. Which is why the Southern Nevada Water Authority (SNWA) is rushing to complete a new intake pipe for Lake Mead, Las Vegas’s main water source.

Initiated in 2008, the project was originally slated for completion in 2012. But the $817 million venture has not gone smoothly. In July 2010, work on the three-mile tunnel was cut back when crews struck a geographical fault, releasing water and muck into the construction area. Attempts to stabilize the area failed, forcing the team to begin excavating in a different direction. The project is now expected to be finished in July 2015. “We’re trying to get this done before the lake drops low,” says Erika Moonin, the engineering project manager for Vegas Tunnel Constructors. “We start seeing water-quality impacts at low lake elevations with our existing facilities.”

According to Moonin, every summer a thermocline—a distinct layer of warmer water, which traps wastewater and contaminants within it—forms near Lake Mead’s surfaces. As the lake level falls, that layer gets closer to the intake pipes, making it more difficult and more expensive to treat drinking water.

And it’s not just Lake Mead and Las Vegas that must cope with the drought. The 1,450-mile Colorado River irrigates nearly 4 million acres of land and provides water to 30 million people in seven states: Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, New Mexico, Arizona and California. (Mexico and 23 Native American tribes also share water rights.) The area’s driest two-year-period on record spanned from 2012 to 2013, and the entire river system is now 50 percent full (or empty, depending on how you choose to view it).

Every year, the water manager at each reservoir along the river determines how much water can be sent downstream, based on how much precipitation has flowed into the system. Lake Powell, which sits on the Colorado on the border between Utah and Arizona, is the country’s second-largest reservoir. It dropped a combined 60 feet in 2012 and 2013. This year, because it currently sits so low, Powell will make its lowest water release since the basin started filling in the 1960s.

That means less water going into Lake Mead, the nation’s largest man-made reservoir, which sits farther down the Colorado, between Nevada and Arizona. That’s presenting a challenge for thirsty places like Las Vegas, which gets 90 percent of its supply from the lake.

In fact, with Mead at 40 percent capacity as of June and dropping, the city could be down to its last straw. Currently there are two intake pipes “sipping” the liquid gold out of the lake and into the city’s waterworks, but if the lake, now down to 1,084 feet, drops to elevation 1,065, serious problems will ensue. That’s because Intake 1, located at elevation 1,050, will no longer be able to effectively pump water. Projections made by the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Reclamation predict that the lake will fall to 1,068 feet by June 2015. That would mean major difficulty pumping from Intake 1—not to mention water-quality concerns.

The new intake pipe was supposed to pick up the slack, but the economic crisis in 2009 forced the SNWA to postpone building its new accompanying pumping station. Instead, the authority opted for an emergency connection between Intake 3 and the two existing pipes. In June 2014, the connector tunnel was completed .

Bronson Mack, a public information officer for the SNWA, admits that the emergency connection won’t fully compensate for the loss of water should Intake 1 go down. “But it does buy us at least a few years of operation,” and, he adds, it will help them continue to defer the costs of building that third pumping station.

That may sound promising, but it only points to the extreme measures water utilities are going to need to take in a drier future to keep the taps flowing.

A millennium ago, when the Anasazi lived in the river basin, they simply moved to wetter regions when epic droughts hit. But that’s not an option today for residents of Phoenix, Las Vegas and Los Angeles. And, in 2014, human-caused climate change is making normal dry spells even worse. “You add warming temperatures to a drought, and it becomes even worse,” says Toby Ault, a climate scientist and assistant professor at the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at Cornell University.

One reason is that the heat tends to send more moisture into the atmosphere because of higher evaporation rates. A recent study by Benjamin Cook, “Global Warming and 21st Century Drying,” argues that this increase in evaporation could end up making a larger part of the West more susceptible to a megadrought.

In fact, Ault’s team at Cornell has come up with a frightening estimate of future megadrought risks: There’s an 80 to 90 percent chance of a 10-plus-year drought occurring this century, with a realistic threat of an epic 30- to 40-year dry spell. Unfortunately, water managers won’t even know if such a drought is happening until many years pass.

Connie Woodhouse, a researcher at the University of Arizona’s Tree Ring Lab, says droughts can be evaluated only by looking back. “It’s a little bit hard at this point to say, ‘Yeah, we’re at the beginning of a megadrought or we’re not.’ You have to watch as things unfold,” she says.

But it doesn’t take a crystal ball to realize just how serious the current Western dry spell is, and cities are starting to respond. Las Vegas uses a lot of water for its size (think of the fountains at the Bellagio), but it has made significant improvements in water efficiency. For example, the city now recycles 100 percent of the water it uses indoors (in bathrooms, kitchens, etc.). And despite a tripling of the population since 1989, per capita water consumption has decreased over 40 percent—thanks largely to the city’s Water Smart Landscapes program, which pays residents $1.50 a square foot to remove turf. “If you had an 18-inch-wide piece of sod, you could roll that piece of sod 85 percent of the way around the globe,” says John Entsminger, general manager of the SNWA. “That’s how much grass we’ve taken out.”

Doug Kenney, director of the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy and the Environment’s Western Water Policy Program, at the University of Colorado Law School, also gives Las Vegas water management high marks. “People like to cast a critical eye on Las Vegas regarding water use, but in general, it has shown a lot of leadership in municipal water conservation, and it has been one of the strongest voices calling for improved management of the river as a whole,” he says.

As for those Bellagio fountains, if you were ever mesmerized by the 500-foot geysers, you can assuage your guilt, knowing they’re fed from an old well once used to irrigate the golf course at the Dunes.

Still, more than 50 percent of Vegas’s green carpets remain. Entsminger admits the area has plenty of work left to do. “We’re proud of our conservation plan, but we’re not declaring victory,” he says.

That said, with just a 1.8 percent allotment, Nevada has the smallest entitlement of the seven states that share the river. The real issue, says Kenney, is “the fact that the Law of the River promises more water to seven states and Mexico than exists currently and is expected to ever exist.” He’s referring to a series of agreements, laws and court decisions made since the original Colorado Compact of 1922, which determined how much water would be allotted to each of the states.

Things would get a lot simpler if some serious rain could be counted on. There is a glimmer of hope in that regard, thanks to a possible return to El Niño conditions this coming winter. With above-average sea surface temperatures developing over much of the eastern tropical Pacific, the National Weather Service has indicated the potential for enhanced rainfall in parts of the West.

But even if next year turns out wet, that won’t be enough to fill those reservoirs. Dan Bunk, a senior hydrologist for the Bureau of Reclamation, says that would take an extremely wet period, like the one that occurred from 1982 to 1985. “If you were to simulate that four-year period in our models, you could fill the system back up in about four to five years. But you’re basically talking about repeating the highest four-year period on record,” Bunk says.

The chance of that happening is slim. Ault says we need only combine the long periods of aridity during the last few millennia with future climate models to understand we’re destined to face some serious droughts this century—thus increasing the need for water departments to tackle expensive, complex and time-consuming projects like Intake 3.

What’s more, Kenney points out that lowering intakes is just a coping strategy that doesn’t solve long-term water woes. “Make no mistake: If demands are allowed to continue exceeding supplies, then building a deeper straw only delays a day of reckoning. If a megadrought is on the horizon, then the money being spent by Las Vegas on the new intake is to buy time to find a solution; it’s not the solution itself.

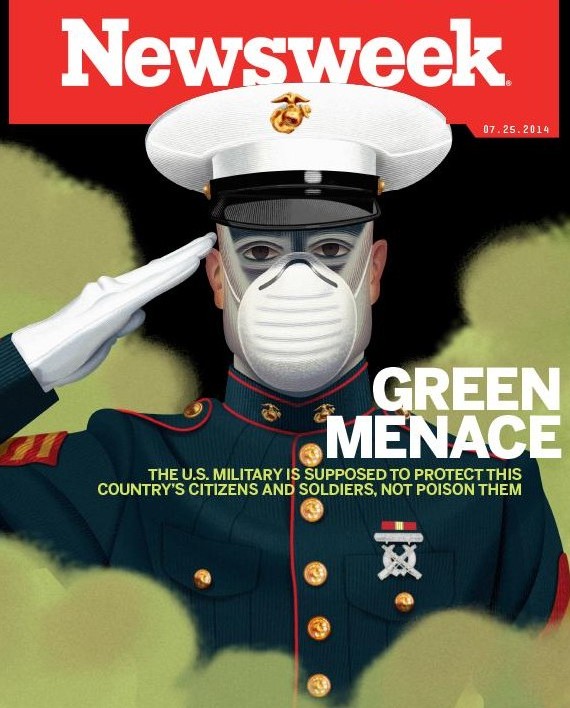

Source: Newsweek.

Pure Water Gazette Fair Use Statement

![rainbarrelgreen[1]](http://www.purewatergazette.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/rainbarrelgreen1.jpg)